05 July 2008

NASA recently published an amazing image, acquired by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The image shows a very thin section of the remnant of a dead star. The star’s remains were hurled into the interstellar space by a tremendous stellar explosion, termed supernova, over 1,000 years ago.

A supernova occurs when a massive star ends its evolution in a catastrophic explosion, or alternatively, when a white dwarf star accretes material from a nearby companion star, leading to the explosion of the white dwarf. On rare occasions, a supernova occurs due to the collision of two stars.

On 1 May 1006 A.D., a brilliant new star shone in the skies, and was recorded by astronomers in Egypt, Iraq, Europe and the Far East. The star is designated SN 1006, a luminous supernova explosion of a white dwarf nearly 7,000 light-years away.

SN 1006 was probably the brightest star ever recorded in history; it outshone all celestial objects except for the Sun and the Moon. It was visible even in the daytime skies for weeks, and remained visible to the unaided eye for at least two and a half years, before fading below naked-eye visibility. Ali ibn Ridwan (c. 988-1061), the Egyptian astronomer, left a valuable document of his observations of SN 1006. He mentioned the supernova shone low in the southern sky, and its brightness was about one quarter that of the Moon.

In the mid-1960s, radio astronomers detected for the first time a nearly circular ring of material at the position of the supernova. The apparent size of the ring was similar to that of the Full Moon (approximately 0.5 degrees across). The size of the remnant implied that the blast wave from the supernova had expanded at an incredible speed of nearly millions of kilometers per hour since the explosion.

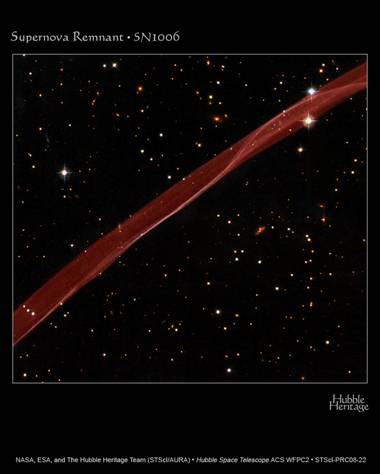

In 1976, the first detection of extremely faint optical emission of the supernova remnant was reported, but only for a filament located on the northwest edge of the radio ring. A tiny portion of this filament is revealed in detail by HST observation. The twisting ribbon of light highlights locations where the expanding blast wave is slamming into very tenuous surrounding gas.

The hydrogen gas heated by this rushing shock wave glows in visible light. Therefore, the optical emission provides astronomers with a detailed "snapshot" of the actual position and geometry of the shock front at any given time. Bright edges within the ribbon correspond to places where the shock wave is viewed exactly edge on to our line of sight.

Now we know that SN 1006 is nearly 60 light-years across, and it is still expanding at roughly 10 million km per hour. Even at this mind-boggling speed, however, it takes years to observe any significant outward motion of the shock wave against the distant background stars. This is due to the vast distance of SN 1006.

The HST image reveals that the supernova would have occurred far off the lower right corner of the image, and the expansion would be toward the upper left.

SN 1006 belongs to our Galaxy, the Milky Way. It is located more than 14 degrees from the galactic plane. Most of the white dots are foreground or background stars in our Galaxy. Many background galaxies (orange extended objects) are also visible in the image.

This image is a composite of images obtained with Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys in February 2006, and Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 images in blue, yellow-green, and near-infrared light taken in April 2008.

Further Reading

Hubble Site

http://hubblesite.org/

Aymen Mohamed Ibrahem

Senior Astronomy Specialist