13 September 2008

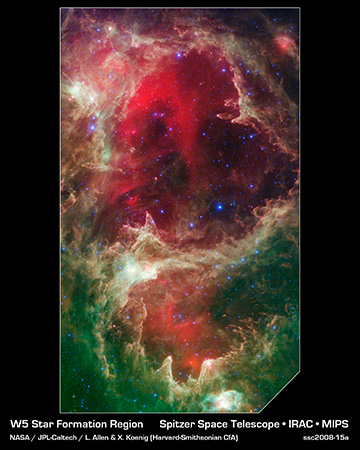

A new image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope (SST) reveals stellar evolution amidst a rich population of stars. The exquisite infrared picture shows a colorful nebula (cosmic cloud), known as W5, studded with multiple generations of dazzling stars.

It also yields dramatic new evidence that massive stars, through their fierce winds (streams of particles) and radiation can stimulate the birth of new stars.

"Triggered star formation continues to be very hard to prove," said Xavier Koenig of the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "But our preliminary analysis shows that the phenomenon can explain the multiple generations of stars seen in the W5 region." Koenig is principal author of a study detailing the findings.

The most massive stars in the universe form within dense clouds of gas and cosmic dust. The masses of these hefty stars range from 15 to about 60 times the mass of our Sun. They emit intense electromagnetic radiation, and shed some of their material in the form of winds, due to their huge masses. Over time, both the stellar wind and radiation erode surrounding cloud material, sculpting growing cavities.

Astronomers have long speculated that the carving of these cavities causes gas to compress, forming successive generations of new stars. As the cavities expand, more and more stars form along the cavities' rims. The result is a radial "family tree" of stars, with the oldest in the middle of the cavity, and successively younger stars farther out.

Evidence for this theory can be found easily in pictures of star-birth regions. For example, in the new Spitzer image of W5, the most massive stars, shining as blue dots, are at the center of two hollow cavities, and younger stars (pink or white) are embedded in the elephant-trunk-like pillars as well as beyond the cavity border. However, it is possible that the younger stars just happen to be near the edge of the cavities and were not triggered by the massive stars.

Koenig and his colleagues set out to test the triggered star-formation theory by studying the evolution of the stars in the W5 region. They used SST's infrared detectors to peer through the dusty clouds and get a better view at the stars' various stages of evolution. They found that stars within the W5 cavities are older than stars at the rims and even older than stars farther out beyond the rim. This sequence of evolutionary phases provides some of the best evidence yet that massive stars may give rise to younger generations.

"Our first look at this region suggests we are looking at one or two generations of stars that were triggered by the massive stars," said co-author Lori Allen of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "We plan to follow up with even more detailed measurements of the stars' ages to see if there is a distinct time gap between the stars just inside and outside the rim."

Stellar evolution theories show that massive stars evolve rapidly. It is expected that within a few million years from now, a short period by the cosmic time scale, the massive stars in W5 will die in titanic explosions, known as supernovae. When the supernovae occur, they will destroy some of the young nearby stars, whose birth was stimulated by the supernovae progenitors.

W5 spans an area of sky equivalent to four times the breadth of the Full Moon, and is about 6,500 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. The Spitzer picture was taken over a period of 24 hours. The color red is from heated dust that pervades the region's cavities.

Green highlights the thick clouds, and white knotty areas are where the youngest stars are forming. The blue dots are older stars in the star-forming cloud, as well as unrelated stars beyond and in front of the cloud.

References

SST Website

http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/Media/releases/ssc2008-15/release.shtml

Aymen Mohamed Ibrahem

Senior Astronomy Specialist