Back in 2010, a series of bloody shark attacks terrorized the normally serene beaches of Sharm-Elsheikh. In the span of ten days, sharks severely injured four tourists and mauled a fifth to death; all attacks occurring near the shoreline. The attacks were so ferocious that experts were at a loss explaining the unprecedented behavior; particularly why the sharks launched multiple attacks so close to shore.

Although there has been no further bloody attacks reported, to this day, the reason for the horrific attacks remains a mystery that overshadows the reputation of the once idyllic holiday destination. As we recount the events that occurred at Sharm‑Elsheikh and attempt to contemplate the attacks retrospectively, can we get closer to finding out why the sharks attacked? More importantly, should we be worried that they might return to attack again?

To answer these questions, we have to first understand what exactly happened at Egypt’s most favored resort.

The Attacks

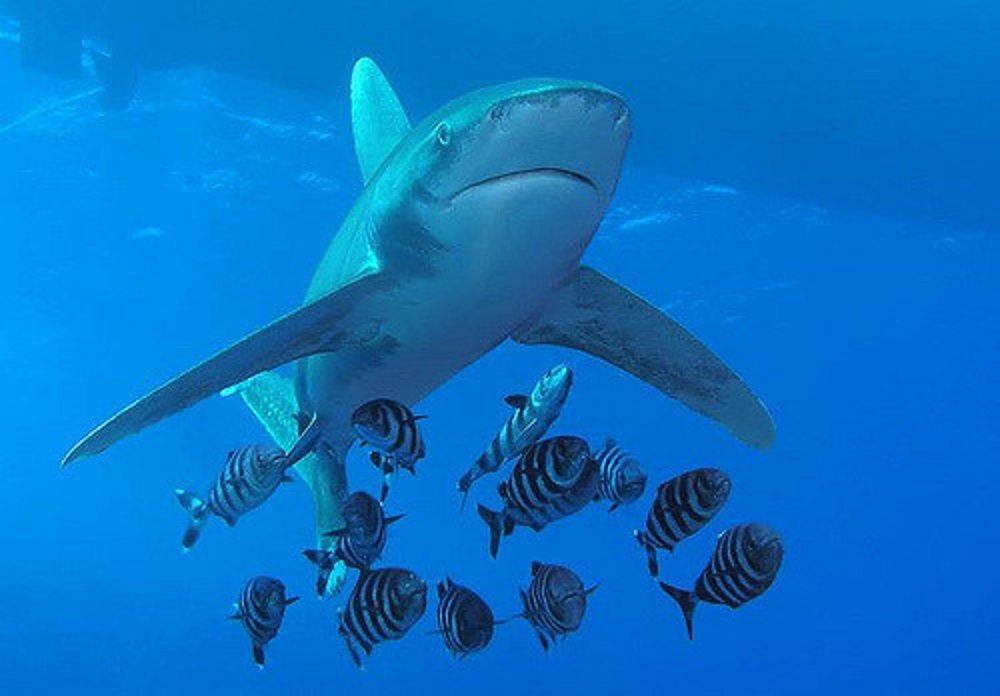

In 2010, three foreign snorkelers were attacked on 30 November and 1 December, suffering serious injuries and mutilation. The attacks were first blamed on an Oceanic White Tip(1) shark, and then on another of the same type and a Mako shark(2). The Ministries of Environment and Tourism responded by shutting down diving sites in Sharm-Elsheikh and launching a wide shark hunt; the animals believed responsible were caught and the coastline was declared safe. Days later, an elderly German tourist was killed by yet another shark attack.

This scenario sounds like the plot of the 1975 Jaws, a film that terrified cinema-goers of the sea for years afterwards. Yet, these events were real, and cannot be attributed to a group of psychotic sharks suddenly turning murderous and developing a taste for human flesh.

Although both species believed responsible for the attacks are categorized as a threat to humans, they rarely attack and are credited with only 16 reported human attacks across the world since records began. Richard Pierce, Chairman of the Shark Trust and the Shark Conservation Society, said: “This spate of attacks is unprecedented. For either of these species to make repeated attacks on humans is unheard of. They simply do not go around attacking people for fun; neither do they seek out humans as food. As the oceanic name suggests, they are not normally found close to shore; they prefer the open ocean”.

This means that some kind of trigger must have been responsible for them being attracted inshore and repeatedly attacking humans. With so much influence we humans are imposing on the ecosystem nowadays, the trigger was almost certainly something we had thoughtlessly done.

Blame the Sheep

The experts and marine biologists who were flown in to assess the situation had many theories as to what may have triggered the attacks. Perhaps the most plausible hypothesis suggested was that they were probably the result of dumping sheep carcasses in the sea.

There were allegations about large cargoes of dead sheep being dumped in the sea after dying on route to Egypt from Australia. Although Australia’s livestock export manager attested that, to his knowledge, there had been no Australian livestock vessels passing through there in that 10-14 day period, there were witnesses who claimed they saw the carcasses being dumped in the sea. The theory is that the carcasses acted as bait to the sharks, driving them close to shore, where they came into contact with the victims.

Blame the Tourists

Even though the practice is illegal, tour guides have been known to throw shark bait into the water to lure sharks closer to boats so tourists can get a glimpse of the creatures, especially during glass-bottom boat rides that take tourists out fish-spotting for the day. Moreover, according to locals, dive schools sometimes bait sharks during diving lessons to impress clients and outcompete with other dive schools for customers.

The practice, known as "chumming”, is said to disrupt marine ecology and associate man with food in the minds of sharks, which might have led to the attacks.

Blame the Hunger

Some local environmentalists support a different theory; they claim the sharks were simply hungry. The theory is that overfishing in the open ocean led to the depletion of fish stock that sharks depend on for survival, which forced them to venture further ashore and seek an alternative food source.

Ian Fergusson, a Shark Biologist involved with the UK Conservation Group ‘Shark Trust’, supports this theory: “While any degradation to the ecosystem of the local reef would not necessarily affect the Oceanic White Tip shark because it is outside its natural habitat, this could point to a larger issue of general offshore fishing of tuna and other big fish, whittling down and influencing the food chain; thus, disrupting the sharks’ ecosystem”.

Blame the Man

The experts were unable to pin down the reason for the attacks to a single one, and unfortunately, neither can we; but, we can conclude that the attacks were not a random case of sharks gone wild, and that they were the result of a combination of Man-induced factors. Overfishing, illegal dumping and chumming, combined with unusually high temperatures resulting from global warming, and a large number of tourists increasing the odds of an encounter, have all contributed to the unprecedented attacks.

Killing the sharks is certainly not an option, not least because they are a national treasure, but also because they are an essential part of the marine ecosystem. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 30 million to 70 million sharks are killed in fisheries per year, and one-third of open-water shark species are facing extinction.

The team of experts suggested some recommendations in hopes of preventing further attacks. These included an immediate stop to the culling(3) of sharks; enforcement of bans on feeding marine life; environmental and emergency education for all diving personnel, crew and beach staff; environmental awareness for tourists and the public; and enforcement of existing laws against illegal fishing.

With the government putting into effect these recommendations, it is highly unlikely that such ferocious attacks will be repeated. However, even with strict marine regulations, the number of unprovoked shark attacks has grown at a steady pace over the past century, with each decade having more attacks than the previous, as recorded by the International Shark Attack File (ISAF).

This should be a reminder that the seas are the shark's natural habitat and that we are visitors there. We can never make the sea completely safe for us, but we can certainly decrease the odds of such terrifying attacks, starting by not messing with the shark’s natural environment.

For all of you out there, heading for the Red Sea for your holidays, we can set our minds at ease by reading the next column.

What to do if you Encounter a Hungry Shark

Adapted from the writings of Ian Fergusson, Shark Biologist and Patron of the Shark Trust

Your first aim is not to encounter a shark at all:

- STEER CLEAR of river mouths and estuaries, areas populated by seabirds, as well as dolphins or seals. Swimming in these areas is like entering a lion cage and wandering over to his food, then wondering why the lion attacked you.

- STAY on the beach side of the reefs, close to shore; the depth can plummet from 10 to 500 meters very quickly on the seaward side. Remember to snorkel in groups to deter sharks.

- AVOID swimming in waters with poor visibility, and do not go in before dawn or after dusk because sharks are most active in the dark. It does not matter what color you are wearing; you appear as a silhouette to a shark.

- AVOID bright-colored clothing, such as orange and yellow or shiny jewelry, which may appear to be like fish scales; sharks see contrast very well.

- NEVER snorkel or swim if you have an open wound, and leave the sea immediately if you cut your feet on the reef.

If you find yourself in the company of a shark:

- KEEP IT IN SIGHT, while moving swiftly and smoothly towards the shore without making a big splash or commotion.

- NOTICE ITS BEHAVIOR. If its posture is stiff and its mouth is opening and closing as it swims towards you, change tactics; this could be because it thinks you are a dolphin, or because you are in its territory, or because it is curious.

- BE AGGRESSIVE; ‘playing dead’ does not work here. Defend yourself with whatever weapons you can, and avoid using your bare hands or feet if possible. If not, aim for the gills and eyes, which are the most sensitive spots; punch and kick with all your might.

- NEVER SURRENDER; keep pummeling the shark’s eyes and gills until you either die or the shark goes away. If you create enough trouble for the shark, it will eventually give up and find something easier to eat.

Glossary

- Oceanic White-Tip Shark: Carcharhinus longimanus is a large pelagic shark inhabiting tropical and warm temperate seas. Its stocky body is most notable for its long, white-tipped, rounded fins.

- Mako Shark: Isurus is a genus of mackerel sharks which includes two living species inhabiting offshore temperate and tropical seas worldwide; the common short-fin Mako shark and the rare longfin Mako shark. They range in length from 9 to 15 feet, and have an approximate maximum weight of 1,750 lbs. The Mako shark is capable of swimming up to 40 mph and jumping up to 24 ft. in the air.

- Shark Culling: Reducing the population of sharks in a certain area by selective slaughter, usually done in areas where shark attacks have become a problem.

References

bbc.co.uk

telegraph.co.uk

dailymail.co.uk

treehugger.com

*Published in the PSC Newsletter, Summer 2012 Issue.