The German-born English astronomer, Caroline Herschel, was the first woman to discover a comet, to be officially recognized in a scientific position and get paid for her contribution to science, to be awarded a Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, and to receive honorary membership into Britain’s prestigious Royal Society.

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was born in the town of Hanover, Germany, on 16 March 1750. At the age of ten, Caroline was struck with typhus, which stunted her growth, so that she never grew past 120 cm. Her family assumed that she would never marry; her father wished her to receive an education, but her mother opposed this. Her father sometimes took advantage of her mother’s absence to teach her directly or include her in her brother’s lessons.

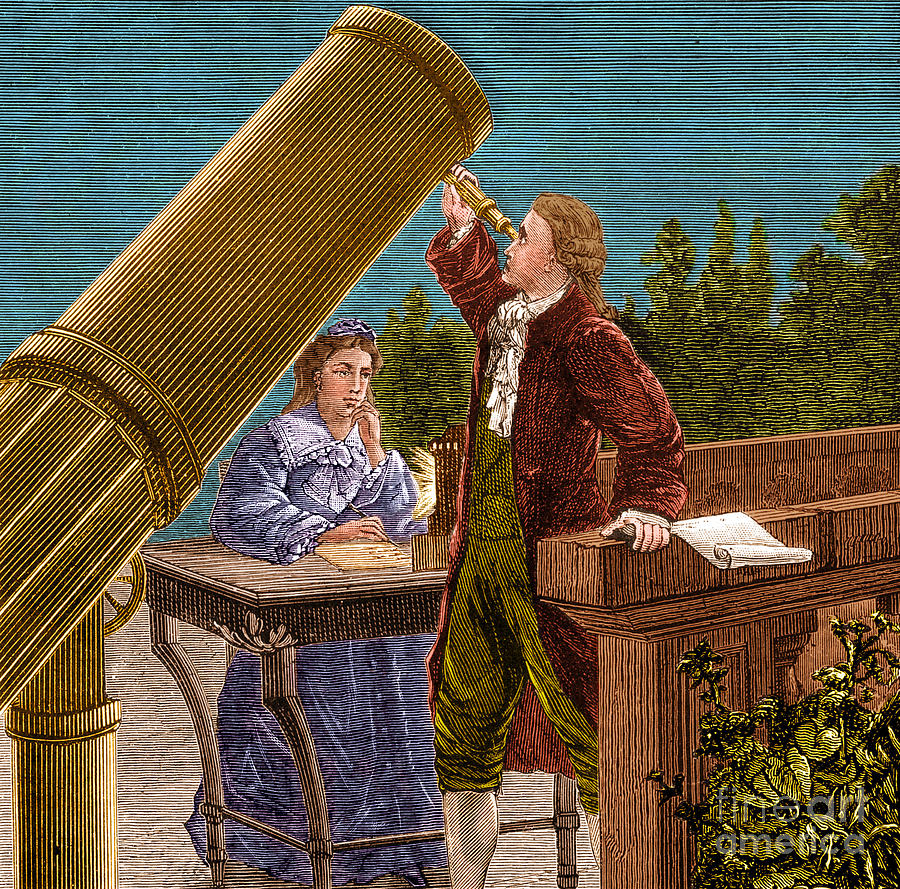

When Caroline was 22 years old, she found her way out from Hannover with the help of her brother William, who had moved to England seven years earlier and made a life for himself as a musician. William exhibited a special interest in astronomy as a hobby; he would then explain to Caroline the amazing things he learned about the stars. Caroline grew fascinated with her brother’s new hobby, and she urged him to train her to be his assistant. With time, William became known for his work on high performance telescopes, and Caroline found herself supporting his efforts.

Caroline spent many hours polishing mirrors and mounting telescopes in order to maximize the amount of light captured. Although she never memorized her multiplication tables, it was she who did the complicated calculations from her brother’s observations. She learned to copy astronomical catalogues and other publications that William had borrowed; she also learned to record, reduce, and organize her brother’s astronomical observations. She recognized that this work demanded speed, precision and accuracy.

In 1781, while observing the night sky with the powerful telescope they built together, Caroline and William discovered the planet Uranus; this was the point that turned astronomy into their livelihood. Expectedly, it was William who was greatly celebrated by the scientific society for this discovery, while Caroline’s contribution was rather slighted.

William feared that Caroline’s name would remain unmentioned if she continued working under his supervision; at his suggestion, Caroline began to separately make observations on her own in 1782. She spent long hours every day observing the sky with her 27‑inch focal length Newtonian telescope, detecting a number of astronomical objects between 1783 and 1787. Most notably, she made an independent discovery of M110 (NGC 205), the second companion of the Andromeda Galaxy.

During the following ten years, Caroline successfully discovered eight comets; the first being discovered on 1 August 1786. Her comet came to be known as the “first lady’s comet” and brought with it the fame that secured her a place in history books. In recognition of her work and as an encouragement for her to move forward, in 1787, she was granted a salary of £50—equivalent to £5,700 in 2016—by the King of Great Britain, George III, for her work as an astronomer, making her the first woman paid for scientific services.

Following the discovery of her eight comets, she studied the “star catalogue” published by the great English astronomer John Flamsteed, compiling and cataloguing over 3000 stars. She conducted a long 20-year survey of the night sky to cross-index this star catalog, and eventually submitted more than 550 stars that had not been included in the original version.

In the wake of William’s death in 1822, Caroline returned home to Germany and worked on cataloguing every discovery she and William had made. During her lifetime, she received several awards including the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society. Many of the comets she discovered bear her name; the asteroid 281 Lucretia was named after her second given name, and the crater C. Herschel on the Moon is named after her. Moreover, two of the astronomical catalogues published by her are still in use today.

Thanks to her brother William, Caroline is one of the few historical women astronomers of her time whose life is well documented and discoveries well recognized. She passed away on 9 January 1848; the inscription on her tombstone reads: “The eyes of her who is glorified here below turned to the starry heavens”.

*Published in SCIplanet, Women and Science (Spring 2016) Issue.

References

www.nasa.gov

www.britannica.com

www.womanastronomer.com