| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |34 |review |

|

Outbreaks are a much larger

menace today than they were just three decades ago. They are larger in

two ways.

First, changes in the way

humanity inhabits the planet have led to the emergence of new diseases

in unprecedented numbers. In the thirty years from 1973 to 2003, when

SARS appeared, 39 pathogenic agents capable of causing human disease

were newly identified.

The names of some are

notoriously well-known: Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and the organisms responsible

for toxic shock syndrome and legionnaire’s disease. Others include new

forms of epidemic cholera and meningitis, Hanta virus, Hendra virus,

Nipah virus, and H5N1 avian influenza.

This is an ominous trend. It is

historically unprecedented, and it is certain to continue.

Second, the unique conditions

of the 21st century have amplified the invasive and disruptive power of

outbreaks. We are highly mobile. Airlines now carry almost 2 billion

passengers a year. SARS taught us how quickly a new disease can spread

along the routes of international air travel. Financial markets are

closely intertwined. Businesses use global sourcing and just-in-time

production. These trends mean that the disruption caused by an outbreak

in one part of the world can quickly ricochet throughout the global

financial and business systems. Finally, our electronic

interconnectedness spreads panic just as far and just as fast.

This has made all nations

vulnerable – not just to invasion of their territories by pathogens, but

also to the economic and social shocks of outbreaks elsewhere. Some

experts have gone so far as to state that there is no such thing as a

“localized” outbreak anymore. If the disease is lethal, frightening, or

spreading in an explosive way, there will always be international

repercussions.

The best defence against

emerging and epidemic-prone diseases is not passive barriers at borders,

airports and seaports. It is proactive risk management that seeks to

detect an outbreak early and stop it at source – before it has a chance

to become an international threat. We as a public health experts are now

in a good position to act in this pre-emptive way.

The opportunities are multiple.

The pressures of population growth push people into previously

uninhabited areas, disrupting the delicate equilibrium between microbes

and their natural reservoirs. This creates opportunities for new

diseases to emerge.

Population growth also puts

people in close proximity to domestic animals, creating evolutionary

pressures and opportunities for pathogens to jump the species barrier.

Of the emerging pathogens capable of infecting humans, around 75%

originated as diseases of animals.

Environmental degradation and

changing weather patterns allow known diseases to flare up in unexpected

places, at unexpected times, and with unprecedented numbers of cases.

Intensive food production,

including the use of antibiotics in animals, creates additional

pressures on the microbial world, leading to mutations and adaptations,

including drug resistance.

And we must not forget:

drug-resistant strains of viruses and bacteria also travel well

internationally.

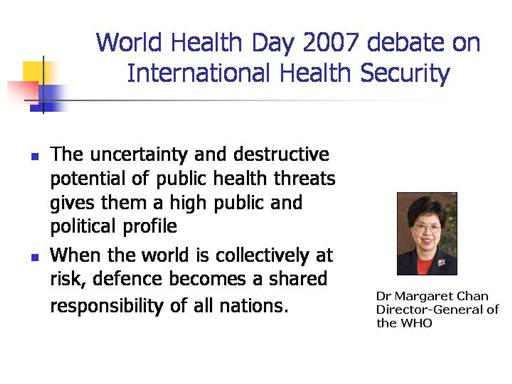

International health security

focuses attention on these complex and interrelated threats to our

collective security.

They reinforce our need for

shared responsibility and collective action in the face of universal

vulnerability, in sectors well beyond health.

|