All advanced photography and projection technologies, as we know them today, have come a long way from their very early beginnings dating back to the Golden Age of Islam when Ibn al-Haytham had his breakthroughs in the fields of light and optics.

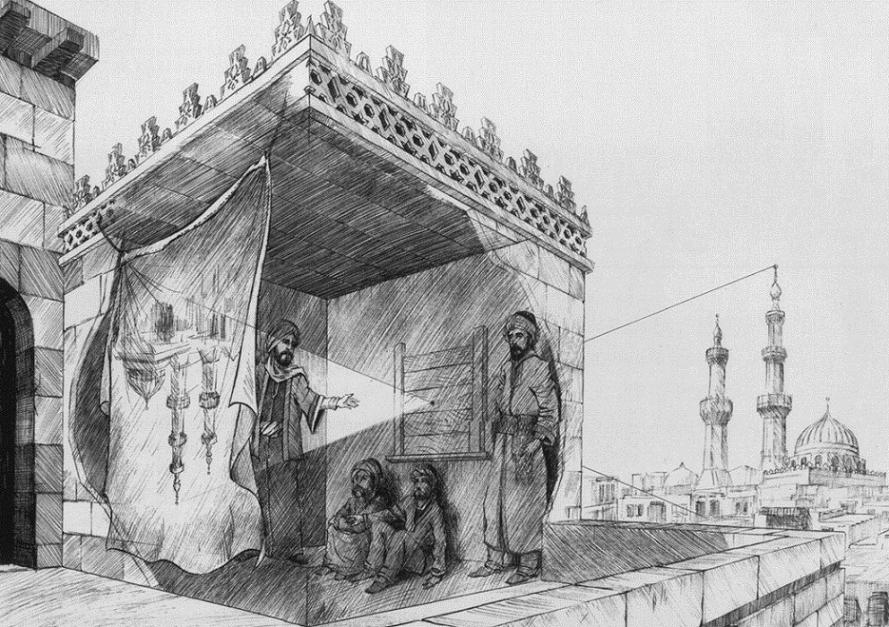

The Camera Obscura

As early as the 11th century, the idea of the camera was already being developed. Ibn al‑Haytham made notes about a camera obscura that used a lens to focus light inside a dark box. An image of whatever the lens was pointed at appeared on a paper surface inside the box. The optical property behind this phenomenon is the same for any type of camera.

The earliest cameras were essentially optical toys, as the simple reflection of an image was something most people had never seen before. The development of modern photography, however, had to wait for other advancements in the fields of chemistry and optics.

Early Camera Evolution

In the 13th century, English scholar Roger Bacon adapted the camera obscura to produce the first pinhole camera, which admitted light through a tiny hole rather than a glass lens. Bacon's version introduced the optical principle to Europe, where photography would eventually be born.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, European scientists continued to work on developing the camera obscura into something more useful. Pinhole cameras made of wood and metal were constructed, and more elaborate mechanisms for focusing the light entering the camera were employed. Experiments were conducted using photosensitive materials to produce photographic images that would soon fade into nothing but indicated that capturing an image was, in fact, possible.

The Birth of Photography

The recording of a negative image on a light-sensitive material was first achieved by the Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. He obtained a camera picture on a polished pewter plate, sensitized with Bitumen, which is a material with an unusual property of hardening in light, not blackening like silver salts; however, its light sensitivity is low, so Niépce needed 8-10 hours of exposure to sunlight.

He named his invention “heliography” which means “sun drawing”, for after dissolving the unexposed parts of the picture in turpentine oil and rinsing the plate, there remained, without the need for any other fixation, a permanent bitumen image of the light drawing; the shadows being indicated by the bare pewter plate.

To avoid a lateral reversal of the view, Niépce placed a prism in front of his achromatic lens. He obtained both components from the optician Charles Chevalier when he purchased his first professional camera. After using glass, lithographic stone and zinc for previous experiments, he ordered the pewter plates.

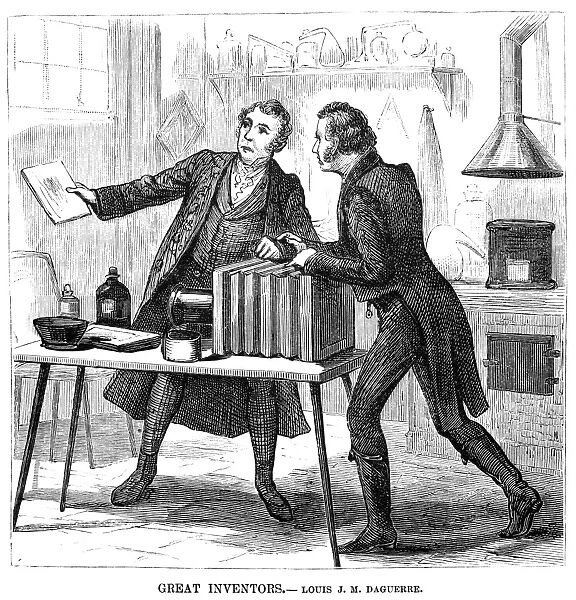

Jacques Daguerre, another Frenchman, developed a process that used copper plates to record an image, and daguerreotypes quickly became the preferred photographic medium for portraits and other subjects. Other processes that used different chemical elements to produce an image, including some that could be tinted or record a partial color spectrum, were also used; the cameras themselves remained largely the same.

*The article was published in the PSC Newslertter, 2nd School Semester 2010/2011.